Lunch & Learn with Craft Lake City

Wed., November 10 at noon | Watch the Recording Here

Craft Lake City’s powerful new exhibition Celebration of the Hand: Safe Not Safe was conceived by Denae Shanidiin with photographs by Jonathan Canlas.

On view from Nov. 1, 2021 to Jan. 31, 2022, Safe Not Safe is an ongoing project exploring Utah’s BIPOC community and their experiences living here. Individuals were asked to present themselves in a space where they felt the safest as well as a space where they did not feel “safe”. They were then photographed in each place and asked to reveal their thoughts and feelings on each location.

Informed by activist Jane Jacobs’ fascination with self-organized urbanism, Celebration of the Hand is a seasonal outdoor exhibition designed to enhance and reflect Salt Lake City’s cultural district through the work of Utah-based artists. Celebration of the Hand is displayed in large frames adjacent to the sidewalks along Broadway (300 South) between 200 West and West Temple, and is open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week free of charge.

The public is invited to a free virtual Lunch & Learn event on Wednesday, November 10 at noon. In this public online event, Kaneischa Johnson, inclusive leadership and culture advocate, will lead a discussion with the two creatives behind the project, Denae Shanidiin and Jonathan Canlas.

“As BIPOC & 2SLGBTQIA Relatives we acknowledge and celebrate our resilience within a world that actively harms us,” says Shanidiin. “These are true accounts of hatred, sexual assault and abuse experienced. Honoring survivors and the actuality of what it is like for BIPOC & 2SLGBTQIA existing within spaces of white supremacy, racism, patriarchy, homophobia, classism, misogyny, xenophobia and domestic violence is important in creating safety and healing.”

The Celebration Of The Hand: Safe Not Safe exhibition features eight works from the ongoing series.

Davina Smith

SAFE | Outdoors

NOT SAFE | Cottonwood Heights Crosswalk

Across the Nation in 2020 BIPOC and BLM protests were very much prevalent and hate crimes were on the rise. It took every effort, energy and commitment to support these causes. Davina Smith whose form of releasing stress, worry and depression is running. The place where she felt was a safe space became the opposite as she was almost intentionally hit by a car driven by a white man. This is said cross walk where the event occurred.

@sltrib | Alixel Cabrera:

Davina Smith remembers the disregard on the driver’s face as he sped toward her, forcing her to leap from the crosswalk and onto the sidewalk for safety. “He looked at me with no care in the world” after she yelled at him through his rolled-down window, she said. “And he was a young white guy, and that scared me. If I didn’t jump out of the way …”

She had been jogging in her own Cottonwood Heights neighborhood, in the bright sunlight, she said, and it seemed like the man had tried to run her over on purpose. On that summer day in 2020, Smith, who is Diné, had made a conscious choice to exercise in a public place in an effort to feel safer. But for Smith and other Indigenous women and women of color, safety is a recurrent worry, despite precautions they might take.

More than 4 in 5 American Indian and Alaska Native women and men have experienced violence in their lifetime, according to a 2016 report from the National Institute of Justice, the majority by at least one perpetrator who is not Indigenous. As a result, ordinary places, such as supermarkets, gas stations and crosswalks can become threatening, a reminder of the harm the person experienced.”

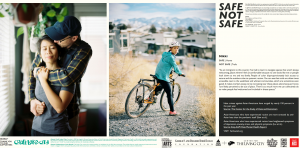

Denae Shanidiin

SAFE | Home, with sister

“There is not much left that hasn’t been stolen by white supremacy or convoluted through capitalism and hoarded by way of invasive powers. However, despite spaces where spirit has been blanketed with whiteness, Indigenous Peoples, Black and Brown Relatives, and people of color remain the experts of their own realities and histories. My people have always been matriarchal, and we embody that within our home. It’s where I feel safe from oppression, patriarchy, and racism.”

NOT SAFE | Utah State Capitol

The Utah State Capitol represents a place where many decisions and laws are made in protection of white supremacy; it is a location where she has been violently harassed without consequence by a white woman in 2020; it also represents ongoing Indigenous genocide and erasure historically supported through the many murals and wall hangings of racist patriarchal figures and pioneers among the halls.

Michelle Brown

SAFE | Home

“I endured physical and psychological abuse in my childhood home(s). I now feel safe in this space that I have curated for myself knowing that no one living under my roof is seeking opportunities to injure me physically or psychologically. It is a victory for me at this point in my life to feel that I have control of my living space enough to feel at ease and relaxed where I live.”

NOT SAFE | Any Gas Station

“I am always cautious when leaving my vehicle when alone. The loss of control I feel when I vacate my locked door often leads to fear and me being highly guarded. I have had men use the opportunity to comment to me on multiple occasions including to tell me that “you would be more beautiful if you smiled”, all while filling their vehicle with gas. I would often ignore the comments and not even finish filling my vehicle and leave as fast as possible. If a stranger tries to engage with me on that level in that space, I do not feel safe. There are too many stories of women last being seen at gas stations, and I don’t want that to be me.”

Raquel

SAFE | Home

NOT SAFE | Childhood Home, Sandy, UT

Raquel, along with her twin sister, Sara, was sadistically abused by her white (former) stepfather at a very young age. Much of the abuse took place in this home.

Sara

SAFE | Home with her baby

NOT SAFE | Childhood home in Herriman, UT

Sara, along with her twin sister, Raquel , was sadistically abused by her white (former) stepfather at a very young age. Much of the abuse took place in this home.

Moroni

SAFE | Home

NOT SAFE | Salt Lake City, UT

“In a car-share/taxi, the driver, after telling him my story of racism, starts to defend racial slurs and starts calling me sand ni**er. I tell him to stop saying that. He doesn’t. I open the door to the moving car and tell him to stop the car. He doesn’t. My humanity could not endure being dehumanized one second longer, and so I rolled out of the moving car. Bruised and bleeding, all I could feel was a sense of freedom, dignity, and self-worth. He turned around and rolled down his window and laughed at me. The police could do nothing. I learned that my dignity is worth more than anything. The next day, I gave the opening prayer at the UT legislature, happiness intact.”

Nikki

SAFE | Home

NOT SAFE | Trails

“As an immigrant to this country I’ve had to learn to navigate spaces that aren’t always welcoming, places where I feel uncomfortable because no one looks like me or people look down at me and my family. People of color disproportionately lack access to nature and the outdoors due to systemic racism. You can see that trails are often times accessible next to the wealthiest and whitest communities, which are sometimes even gated. It makes me feel uneasy to be recreating near these places alone because I know I am likely perceived to be out of place. There is so much more we can collectively do to make people feel welcomed and included in these spaces.”

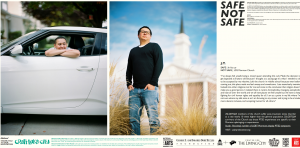

J.T.

SAFE | In his car

NOT SAFE | LDS Mormon Church

“I’ve always felt unsafe being a mixed queer attending this cult. Made the decision to get baptized at 8 years old because I thought at a young age it’s what I needed to do to be accepted by my relatives. Left the church in middle school because even before coming out, this place made me feel uneasy and unwelcome. Late teens/early twenties looked into other religions; not for me and came to the conclusion that religion doesn’t make you a good person. I realized there is racism, homophobia, misogyny, xenophobia and hate all over the world and we all have places we feel unsafe but we have to keep fighting for civil human rights and equality for all. I am at a point in my life where I’m not sure where my safe zone is so I am focusing on my career and trying to be a kinder, more decent, inclusive, an accepting human for all others.”

About Craft Lake City:

Founded in 2009 by Angela H. Brown, Executive Editor of SLUG (Salt Lake UnderGround) Magazine, Craft Lake City® is a 501(c)(3) charitable organization with the mission to educate, promote and inspire local artisans while elevating the creative culture of the Utah arts community through science, technology and art. Craft Lake City strives to further define the term “Craft,” by modernizing the definition for handmade creativity.

craftlakecity.com @craftlakecity

Safe Not Safe (@safe.notsafe) is an ongoing project exploring BIPOC in Utah who were asked to present themselves in a space where they felt the safest at this time in their life as well as a space where they do not feel “safe.”

About the Temporary Museum of Permanent Change:

The Temporary Museum of Permanent Change is a community based, participatory project that uses the ever-changing development processes underway in Salt Lake City as catalysts to animate city life. The Museum engages a variety of audiences using a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach that includes performance art and video production, visual art, urban archaeology, anthropology, local history, existing businesses and ongoing deconstruction and construction processes as spectacles for people of all ages. Together these elements provide teachable moments in our efforts to manage and celebrate change. This museum has no specific address. Rather it is a construction of ideas, installations and illuminations that comprise a new way of seeing our city.

museumofchange.org

About the Center for Living City:

The Center for the Living City’s purpose is to expand the understanding of the complexity of contemporary urban life and through it, promote increased civic engagement among people who care deeply for their communities. The Center provides portals for community engagement through the lens of urban ecology to further the understanding of the interconnected human and ecological systems in our communities. The Center’s multi-disciplinary approach to community engagement is applied through educational programs, collaborative projects, fellowships, on-line portals, workshops and publications.

centerforthelivingcity.org